Protein Morning to Night

Researchers say we need to spread out our protein intake for greater muscle gains.

By Matthew Kadey, MS, RD

Sep 8, 2020

Protein Intake

Two recent journal papers demonstrate why it’s important to consume protein-rich foods throughout the day to build and maintain muscle mass.

A report in Frontiers in Nutrition found that, based on food diaries, older individuals typically do not eat enough high-quality protein at their lunch meal compared with dinner, and this could accelerate age-related losses in muscle mass and functioning. These losses play a role in failing to thrive as people age.

Building new muscle requires a regular supply of amino acids. The process becomes less efficient as we get older, making consistent protein intake at all meals even more vital.

Moving on to a younger generation, scientists in Japan reported on a separate investigation in the Journal of Nutrition. Young men involved in a resistance training program three times a week built higher amounts of muscle mass if they consumed more of their daily protein allotment (1.3 grams per kilogram of body weight per day) at breakfast as opposed to eating little protein in the morning and loading up at dinner.

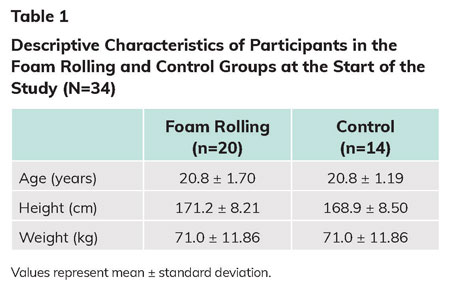

Figure 1

Figure 1

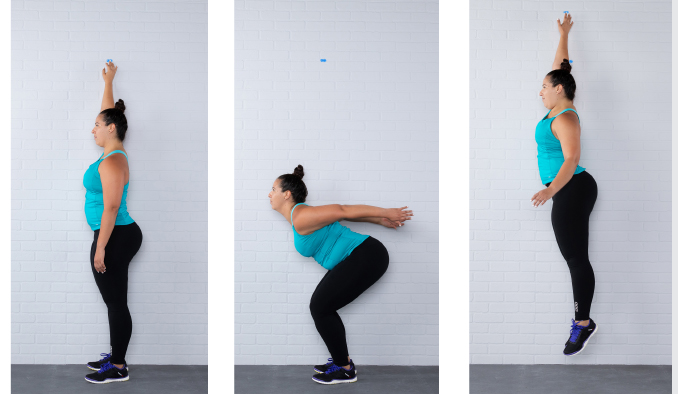

Figure 2

Figure 2 Figure 3

Figure 3

Muscle cramps can stop athletes in their tracks. Although they usually self-extinguish within seconds or minutes, the abrupt, harsh, involuntary muscle contractions can cause mild-to-severe agony and immobility, often accompanied by knotting of the affected muscle (Minetto et al. 2013). And cramps are common; 50%–60% of healthy people suffer muscle cramps during exercise, sleep or pregnancy or after vigorous physical exertion (Giuriato et al. 2018). There is no gender difference with skeletal muscle cramps, but they appear to occur more often in endurance athletes and in the elderly (Naylor & Young 1994).

Muscle cramps can stop athletes in their tracks. Although they usually self-extinguish within seconds or minutes, the abrupt, harsh, involuntary muscle contractions can cause mild-to-severe agony and immobility, often accompanied by knotting of the affected muscle (Minetto et al. 2013). And cramps are common; 50%–60% of healthy people suffer muscle cramps during exercise, sleep or pregnancy or after vigorous physical exertion (Giuriato et al. 2018). There is no gender difference with skeletal muscle cramps, but they appear to occur more often in endurance athletes and in the elderly (Naylor & Young 1994).