Best and Worst Diets of 2020: U.S. News and World Report Annual Rankings

A shocking 70% of American adults are either overweight or obese.* During any given year, an estimated 45 million Americans are “on a diet.” As our waistlines grow, so does the cost of health care. We can no longer afford to ignore the obesity epidemic in this country.

Obesity is strongly associated with a number of chronic conditions including cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, knee osteoarthritis, and some cancers.

With over two-thirds of the population overweight, it’s no wonder the weight loss industry in the U.S. exceeded $72 billion in revenue in 2019. Promises of rapid, life-changing weight loss rarely live up to the hype, and many diets are questionable at best.

What the Experts Said | Definitions Used in Rating the Diets

RANKING THE DIETS

Each year, U.S. News and World Report releases their annual ratings of popular diets. Some diets are deemed safe, nutritious, heart-healthy and effective for weight loss. Other diets are strongly criticized for restrictiveness, nutritional deficiency, safety and sustainability.

For 2020, a team of 25 nutrition experts, including registered dietitians, physicians, and nutrition scientists rated the effectiveness of 35 different diets in the following areas:

- easy to follow

- nutritious

- safe

- effective for weight loss

- protective against diabetes

- protective against heart disease

(Additional details regarding these areas can be found at the end of the blog.)

After scoring each diet in each area, the team ranked the diets in several different categories, including:

- best/worst diets overall

- best/worst weight-loss diets

- best/worst diets for healthy eating

- best/worst heart-healthy diets

- easiest/hardest diets to follow

In the best diets overall category, the Mediterranean Diet came out on top, followed closely by DASH Diet, while the Flexitarian Diet and Weight Watchers Diet finished third and fourth, respectively.

In the best heart-healthy diets category, the Ornish Diet led the pack, followed closely by the Mediterranean and DASH diets.

At the other end of the spectrum, the Ketogenic Diet and the Dukan Diet finished dead last at #34 and #35, respectively. The Alkaline Diet and Paleo Diet also ranked poorly at 28th and 29th respectively, in the best diets overall category.

For heart health, the Whole30 Diet and the Dukan Diet brought up the rear behind other dietary losers like Alkaline, Keto and Paleo.

You might be interested in some of the specific comments made by the expert panel regarding some of these diets:

- MEDITERRANEAN DIET: A Mediterranean style eating plan will showcase healthy foods like whole-grain pita and hummus, salads, fresh fruits and veggies, and beneficial fats found in foods such as salmon, nuts, and olive oil.

- DASH DIET: The Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) plan was lauded for its nutritional completeness and safety, as well as its ability to help prevent and treat hypertension.

- ORNISH DIET: The Ornish diet is nutritionally sound, safe and heart-healthy. While it is great for reversing or preventing heart disease and diabetes, it’s not easy to adhere to the severe fat restriction.

- KETO DIET: With the combination of unusually high saturated fat plus remarkably low carb and fiber content, experts had enough reservations to place the highly-popular Keto Diet way down in the best diets overall category. They seemed equally concerned about the sustainability of this diet and its implications for heart health, citing a 2019 article in JAMA Internal Medicine that concluded “enthusiasm outpaces evidence” when it comes to a keto diet for treating obesity and diabetes.

- PALEO DIET: Slapping the Paleo Diet with multiple low scores, the experts couldn’t accept that entire food groups, like dairy and grains, as well as legumes are excluded, making it hard for dieters to get all the nutrients they need. Paleo was deemed too restrictive to be healthy or sustainable.

- ALKALINE DIET: Experts dealt the Alkaline Diet mostly low scores, pronouncing it difficult to follow and noting that its nutrition profile isn’t ideal. They also noted a lack of research to support claims made by proponents.

DEFINITIONS USED IN RATING THE DIETS

- Short-term weight loss. Likelihood of losing significant weight during the first 12 months, based on available evidence

- Long-term weight loss. Likelihood of maintaining significant weight loss for two years or more, based on available evidence

- Diabetes. Effectiveness for preventing diabetes or as a maintenance diet for diabetics

- Heart. Effectiveness for cardiovascular disease prevention and as a risk-reducing regimen for heart patients

- Ease of compliance. Based on the initial adjustment, satiety (a feeling of fullness so that you’ll stop eating), taste appeal, special requirements

- Nutritional completeness. Based on conformance with the federal government’s 2015-2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans, a widely accepted nutritional benchmark

- Health risks. Including malnourishment, specific nutrient concerns, overly rapid weight loss, contraindications for certain populations or existing conditions, etc.

*Overweight in adults is defined as a body mass index (BMI) between 25.0 and 29.9 kg/m2, while obesity is defined as a BMI greater than or equal to 30 kg/m2. Use this link to calculate your BMI.

Please note that BMI is not a valid indicator of body weight status for individuals who are extremely muscular. However, such individuals make up only a tiny portion of the U.S. population.

Reference

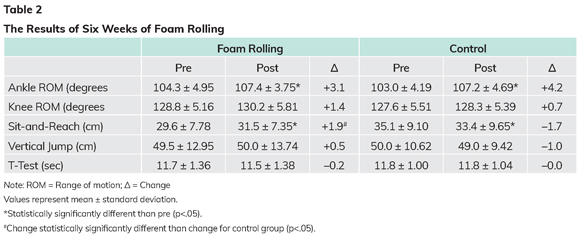

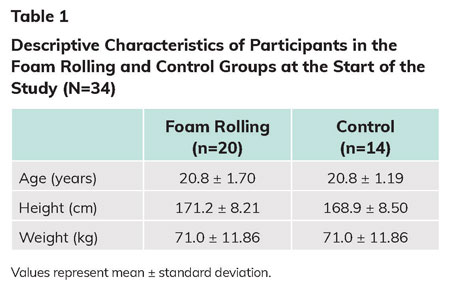

Figure 1

Figure 1

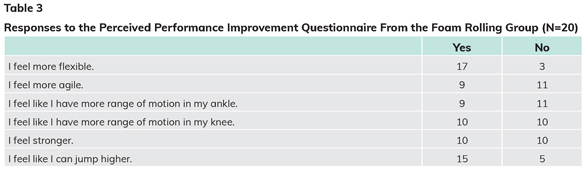

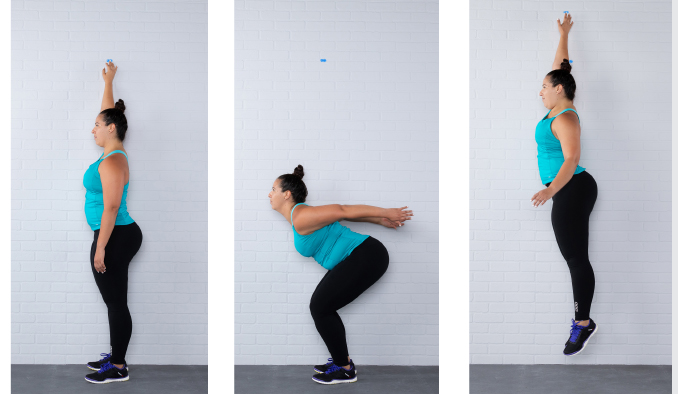

Figure 2

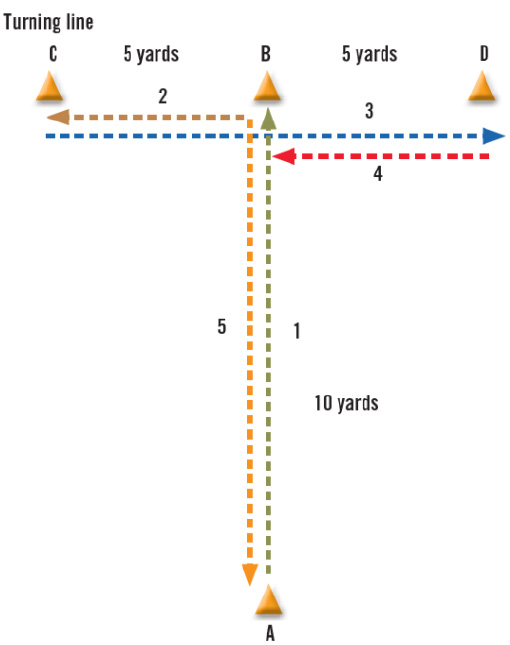

Figure 2 Figure 3

Figure 3