Mark Mayes – Certified Exercise Physiologist

Ponce de León supposedly searched for it in the New World. Herodotus thought it might be near Ethiopia. People have sought a fountain of youth for centuries. Disappointed by the fruitless search for a miraculous pool that could rejuvenate them, people turned instead to elixirs, creams, and cell-rejuvenating drugs—anything that offered glimmer of hope for retaining youth. No one yet has discovered a magic formula that can guarantee a never-ending life span. Diet and exercise researchers, however, have made significant progress discovering ways to extend one’s health span and, thereby, one’s life span.

William Evans, Ph.D. and other researchers from the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Human Nutrition Research Center on Aging at Tufts University (HNRCA) have identified ten biomarkers that may slow down the aging process. “Advanced age is not a static, irreversible biological condition of unwavering decrepitude,” Dr. Evans says. “Rather, it’s a dynamic state that, in most people, can be changed for the better no matter how many years they’ve lived or neglected their body in the past” (14–15). Evans and his colleagues at the HNRCA have outlined the following ten biomarkers of vitality that they believe we can alter through exercise and proper nutrition: muscle mass, strength, basal metabolic rate, body fat percentage, aerobic capacity, cholesterol/HDL ratio, blood/sugar tolerance, blood pressure, bone density and regulation of internal body temperature.

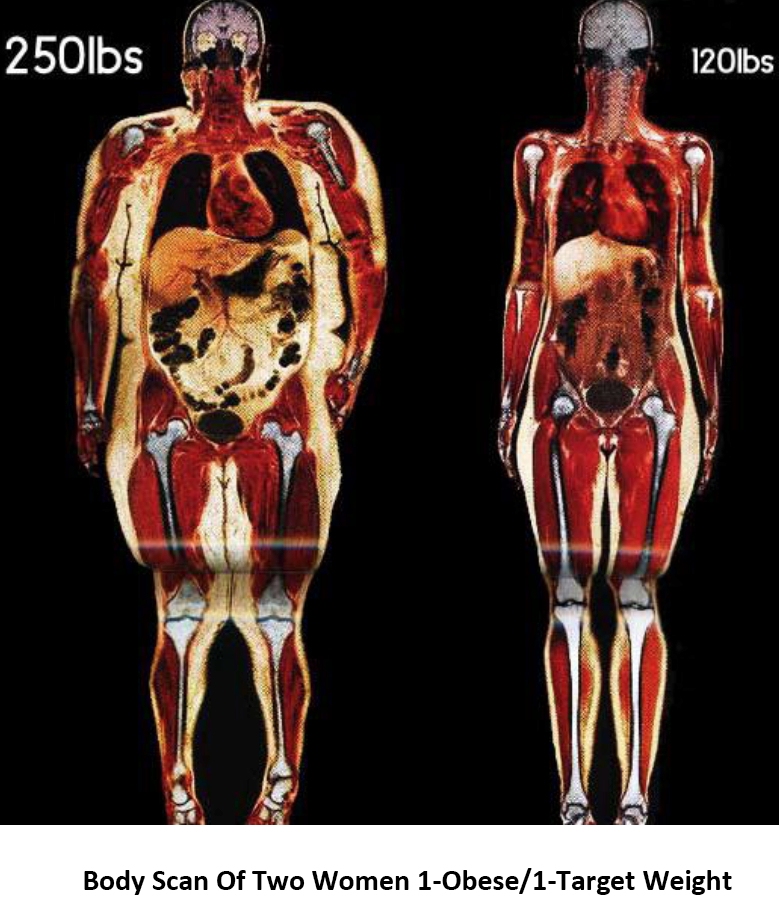

Vital to extending one’s health span, according to Evans, is to concentrate on building muscle while decreasing fat. “Losing weight is the wrong goal,” he points out. “You should forget about your weight and, instead, concentrate on shedding fat and gaining muscle”. One might ask in reply, “I’m 65 years old, and I weigh much the same as I did when I was 21. How would increasing my muscle mass improve or extend my life?” As we get older, we lose muscle tissue at a rate of about 6.6 pounds per decade, and we tend to replace this lost muscle tissue with fat.

Muscle mass, Evans first biomarker, is a key component to other biological functions and in some way, affects the other nine biomarkers. A strong and toned musculature contributes to overall well-being, especially for older adults. Evans and other researchers have found that an increase in musculature:

- increases the body’s metabolism, thus enabling one to burn more calories, which, in turn, helps decrease body fat.

- increases one’s aerobic capacity because denser muscles require additional oxygen; an increased aerobic capacity allows one to be more active.

- increases the body’s ability to utilize insulin, which decreases the chance of developing diabetes later in life.

- helps one maintain a high level of HDL cholesterol— “good cholesterol”—in the blood.

- adds to bone density because strength training and other exercises that increase musculature also stress bones, causing them to become harder.

Many researchers believe that old age is not a time to relax and become idle. Many of the diseases and much of the deterioration that we see in our bodies during our senior years can be prevented or mitigated through exercise. Improvements in Evans’s second biomarker, strength, provide abundant examples.

Among many misconceptions concerning the bodies of older adults are that they cannot improve their strength or that they should not stress their muscles the way that a younger person does. Studies reveal that between the ages of 20 and 70, we lose almost 30 percent of our muscle cells due to inactivity. But research at Tufts has shown that a decline in muscle strength and size is not inevitable. Through strength training, a 70-year-old male could regain the strength of a 20-year-old sedentary male.

Another misconception is that with old age comes an increased likelihood of falling. Evans, however, has demonstrated that the increased incidence of falls in seniors is caused by a decrease in muscle tissue and strength in the legs. Falling in one’s senior years is not due to age but rather to a sedentary lifestyle and a lack of exercise!

Our body’s ability to shed fat and burn calories at rest is called basal metabolic rate (BMR), Evans’ third biomarker. BRM is an indicator of how efficiently our bodies break down tissue and release energy so we can perform daily functions. However, if we take in more fuel (calories) than our bodies can use given our BMR, those calories are stored as fat. After age 20, our BMR drops by about two percent every decade. But studies have shown that no matter what our age, through exercise and increased muscle mass we can stop this decline and even restore our BMR and our ability to burn calories.

The fourth biomarker, percentage of body fat, is directly related to increased disease in older individuals. Excess body fat places an added stress on the heart and increases the chance of stroke and diabetes. Seniors have the ability to lose fat weight—the same as a younger person—through diet and exercise.

Aerobic capacity is Evans’ fifth biomarker. It describes the body’s ability to move large amounts of oxygen through the bloodstream to tissue in a given amount of time, a process that depends on a good cardiopulmonary system—the heart, lungs, and circulatory mechanisms. It is true that aerobic capacity declines 30 to 40 percent by age 65. However, the decline is less pronounced in individuals who exercise regularly. Evans believes that inactivity in seniors reduces the muscles’ oxidative capacity and causes the muscular fatigue that many aging people experience. Exercise physiologists have shown that seniors who start to exercise make greater improvements to their aerobic capacity than younger adults. Certainly, older adults who have been inactive and then begin to exercise have much more room to improve, but it’s important to note that drastic improvements to aerobic capacity can be made even in advancing years.

Everything in the supermarket these days seems to claim to be cholesterol-free; cholesterol is Evans sixth biomarker, but what is it? Cholesterol is a fatty substance produced by the body that is a necessary component in cell membranes and certain sex hormones. It circulates in the bloodstream and is associated with a protein called lipoprotein. There are several types of cholesterol that we need to be concerned with: HDL, LDL, and VLDL. HDL is known as “good cholesterol” because it helps remove plaque or LDL from the arteries. LDL and VLDL are known as “bad cholesterol” because in excess, they can cause a narrowing of blood vessels. As with the other biomarkers, several factors influence our control over cholesterol: genetic make-up, a lack of exercise, obesity, and diet. All but one of these components can be altered through lifestyle changes—we have little control over genetics.

If the body produces too much cholesterol or if one’s diet is high in cholesterol, lipoproteins can start to collect in the body tissue. “Atherosclerosis” is a condition in which excess lipoproteins collect in the blood vessels, and it can eventually develop into heart disease and other circulatory problems. Since the body produces its own cholesterol, it is NOT important that we include it in our diet, but we should be concerned about consuming foods with too much of it. LDL and VLDL levels can be lowered through changes to our diet, but according to the latest studies, HDL can only be increased by lowering body fat and through exercise.

The body’s ability to control blood sugar is the seventh biomarker. With advancing age, the body’s ability to take up and utilize blood sugar decreases. This, in turn, causes the sugar level in our blood to rise, which can develop into mature-onset diabetes, also known as “type 2 diabetes.” By age 70, 20 percent of men and 30 percent of women have an abnormally high blood sugar level. Researchers have found that a decline in sugar tolerance is due to a decrease in the activity level of older adults, an increase in body fat and reduced muscle mass, which leads to a reduction in the body’s ability to absorb insulin. The body produces insulin to regulate the level of sugar in the blood; insulin causes the muscles to use the sugar for energy. The bodies of older adults cannot absorb insulin as readily because their muscle mass has been reduced as they have aged. This lack of muscle mass also continues the cycle of fat storage; excess sugar in the blood that is not used over time is converted to body fat. Age, however, has been shown NOY to decrease one’s ability to influence blood sugar.

Blood pressure is Evans’ eighth biomarker. Increased blood pressure is caused primarily by obesity; smoking; a high-fat, high-salt diet and a lack of exercise. Heredity and race do have some effect on blood pressure, but even considering risk factors beyond our control, blood pressure can be controlled with medication, diet and exercise. High blood pressure, or hypertension, does not have to be a limiting factor for the older person. Scientists at Copper’s Clinic for Aerobic Research in Dallas found that people who maintained their fitness level had a 34 percent lower risk of developing hypertension.

Bone density, the ninth biomarker, is, in part, affected by hormonal changes in women, poor eating habits, deficient calcium absorption and a sedentary lifestyle. Research has shown that an individual’s bone loss is about one percent per year. “Osteoporosis” is a substantial bone loss that increases the risk of bone fractures. Osteoporosis is associated with growing old, but, Evans argues, “Osteoporosis is not a necessary or normal component of aging”. The loss of bone density can be influenced by diet and exercise. Researchers at Tufts found that women who exercise have a higher level of Vitamin D, which aids in the absorption of calcium. They also found that weight-bearing exercises that continually apply stress to the bone cause the bone to become harder. Research to date has not concluded that an increase in calcium intake prevents or slows the effects of bone loss. Tufts researchers combined high-calcium intake with exercise in their study and found that only exercise affected bone loss.

Biomarker ten is the body’s ability to regulate its internal temperature. The body has its own built-in thermostat, but the effects of aging can impair this control mechanism. In a typical older adult, cardiac output, including blood flow to the skin, is reduced. This diminished blood flow to the skin makes sweating harder for the older person’s body because blood flow brings heat to the skin, causing the body to sweat and release that heat. When the body cannot sweat, it cannot release heat as effectively, so it’s internal temperature rises. On the other hand, shivering, which is the body’s way to produce heat, is also decreased in older adults—primarily due to a loss in muscle mass. An inability to shiver makes it more difficult for an older person’s body to raise its internal temperature.

The older adult who stay in shape is better equipped to keep his or her body’s internal temperature at a safe level through increased blood flow to the skin and through an improved BMR.

Unfortunately for us, Herodotus and Ponce de León’s searches were in vain.

There is no magic formula to slow the aging process. The latest research shows, however, that it is possible to close the gap between one’s health span and one’s life span through regular exercise and proper nutrition. Dr. Evans’ ten biomarkers map it all out for us.

Mark Mayes founded Fitness Resources in 1991 and has over 30 years in the fitness industry. He is certified by the (ACSM) American College of Sports Medicine as Exercise Physiologist and ACSM for Seniors. Mayes works with individuals who wish to improve their health and fitness levels.

Reference: William Evans, Ph. D., and Irwin H. Rosenberg, M.D., Biomarkers: The 10 Determinates of Aging You Can Control, (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1991).