Is a Slower Metabolism Really to Blame for Middle-aged Weight Gain?

by Daniel J. Green

by Daniel J. Green

Contributor

We’ve all heard various versions of the same warning as we’ve gotten older:

“Just wait until you reach your 30s. You won’t be able to eat like that anymore!”

“Once you hit 40, exercise gets so much harder!”

“Once you reach your 50s, you’ll gain weight and everything will just start to hurt!”

I’m 48 years old and, to be fair, I can’t eat like that anymore, exercise is harder, I have gained weight and just about everything does hurt—and two years ahead of schedule!

However, the underlying implication of those warnings is that our metabolism is to blame and that the downward trends are all but inevitable. According to a new study, however, that does not appear to be the case.

Research recently published in the journal Science investigated daily energy expenditure throughout the human lifespan. The study was conducted by an international team of researchers, who analyzed the daily caloric expenditure of more than 6,400 people from around the world. The participants’ ages ranged from eight days to 95 years old.

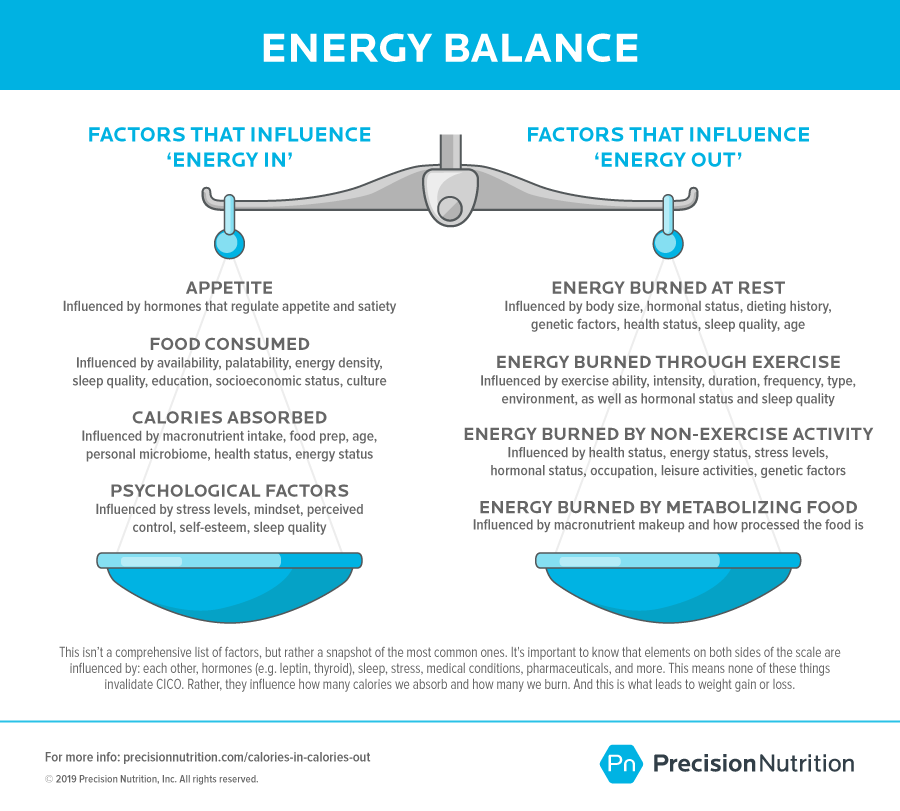

While most large studies have measured basal metabolism—that is, how much energy the body uses to perform vital life-sustaining functions such as respiration and digestion—this accounts for only 50 to 70% of the calories people burn each day. This research also analyzed the energy burned to fuel all other activity, including both planned exercise and activities of daily living. Every calorie expended was accounted for, even those burned while fidgeting or thinking.

What the research team learned runs counter to a lot of the “common knowledge” around the way metabolism changes as we age.

As you might expect, energy needs skyrocket during the first year of life, as babies burn calories approximately 50% faster for their body size than adults. Interestingly, while rapid growth during this period accounts for some of that increased metabolism, the rate of calorie burn is not fully explained by the increase in weight. More research is needed to understand what else is driving the high metabolic rate during that first phase of life. After age 1, a person’s metabolism slows by about 3% per year until they reach their 20s.

Then, and here’s where things become counterintuitive, metabolism levels off and stays relatively consistent until around age 60. When body size was considered, even the growth spurt of adolescence and the changing physiology of pregnancy failed to drive an increase in metabolism. Even after age 60, metabolism declines fairly slowly, by only 0.7% per year.

Stated simply, when body mass is accounted for, metabolism remains virtually unchanged from around age 20 to age 60.

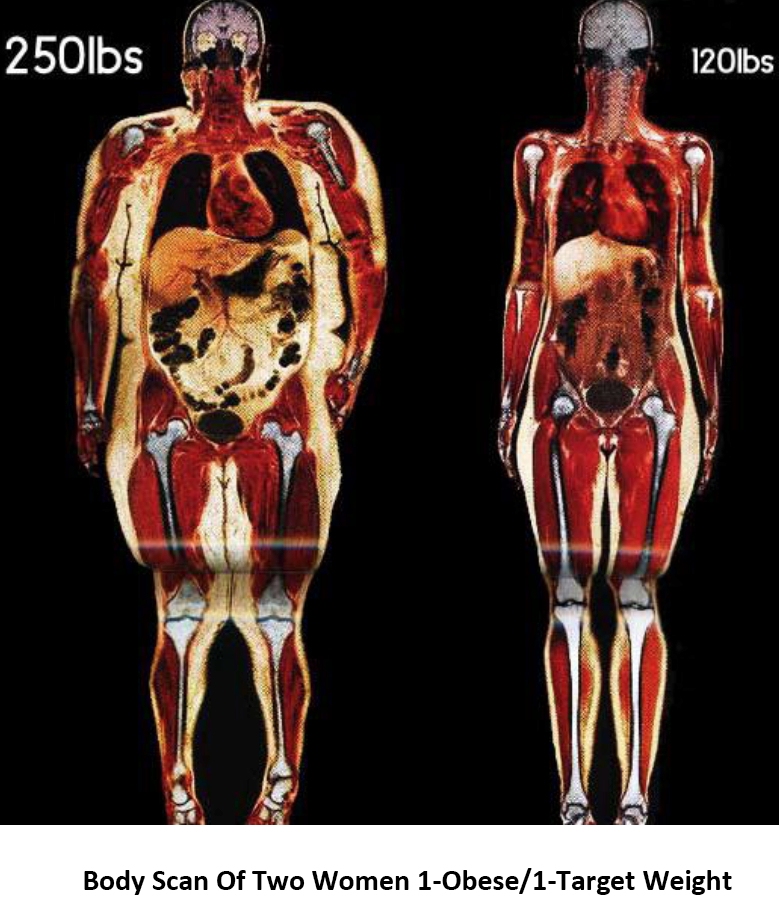

So, what’s going on here? A primary reason for the decline in metabolism is a reduction in muscle mass since muscle burns more calories than fat does. It appears that those physiological changes that take place as we pass from one decade into the next have more to do with lifestyle factors and body-composition changes than they do with a naturally slowing metabolism.

What This Means to You.

Some people may tend to throw their hands up in defeat when they think about getting older. What this research shows is that there is a lot more within their control than they might think. After all, if changes that were once perceived as an inevitable result of a slowing metabolism are actually more connected to our behaviors, then the results of this research should be a source of empowerment for clients.

Metabolism can be described as the chemical changes in living cells by which energy is provided for vital process and activities. As Carrie Myers, a certified mastery-level transformational coach with 30 years of experience in the fitness industry, points out, the fact that metabolism takes place on the cellular level means that it’s impacted by countless factors, some of which are truly out of a person’s control and others that can be positively impacted through behavior change.

Variables that are out of our control include sex, genetics and age. That leaves a seemingly endless list of variables that directly impact a person’s metabolism that health coaches and exercise professionals can address with clients, including not only nutritional intake and physical activity, but also stress, sleep, rest, mental health and the client’s overall happiness.

Myers explains that this holistic approach addresses the whole person. “All of these elements are intertwined,” she says, “so it’s important to look at the big picture of overall health.”

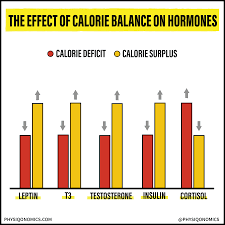

Pete McCall, faculty in the Exercise Science Department at Mesa College, ACE Certified Personal Trainer and author of Ageless Intensity: High-intensity Workouts to Slow the Aging Process and Smarter Workouts: The Science of Exercise Made Simple, agrees with this approach, and says that communication is vital. While conversations about goal setting may not directly touch on a client’s metabolism, health coaches and exercise professionals should discuss the interconnectedness among the variables just described. Yes, energy intake and energy expenditure should be centerpieces of this conversation, but an understanding of the other factors is vital, as well. For example, stress management (or stress mastery, as Myers calls it) and sleep quality are both linked to hormone production, which is directly linked to metabolism.

Education can be empowering, so be sure to take advantage of the goal-setting process and conversations during your sessions with clients to emphasize the importance of overall well-being and the way in which the various elements of physical and mental health are intertwined and impact the way we age.

In Conclusion

Often we believe that weight gain and declining health are just part of the aging process. “They have been led to believe that this is natural and inevitable,” explains Myers. And, on some level this is true, but it’s not due to a rapidly slowing metabolism over the course of our lives. Instead, it occurs primarily because people simply move less as they age.

It’s a vicious cycle and a self-fulfilling prophecy. People begin to gain weight or have some aches and pains, believe it’s part of growing older, so they move less because they think physical activity will exacerbate their pain or is a fruitless pursuit, which means they gain more weight and begin to feel worse.

Take a moment to think about the older people in your life. Some are probably relatively happy and healthy, while others are battling multiple health conditions and struggling to get through the day. McCall and Myers both suggest that health coaches and exercise professionals help their clients recognize the connection between lifestyle and overall well-being, including brain health, functional independence and emotional and mental health. The intention here is not to imply that physical activity and better nutrition are cure-alls, but instead to help clients feel empowered by the fact that their behavior can have a larger impact on their quality of life than they may have previously understood.

Myers says it’s up to health coaches and exercise professionals to help their clients clarify a vision of what they would like their lives to be like as they grow older, and then ask, “How can you establish goals to set you up for that life?”

For McCall, it all comes down to two things: “Stay active and stay strong.” If you do that, a lot of the other elements fall into place, he explains. Performing physical activity, particularly resistance training, can work wonders when it comes to countering the effects of aging and the reductions in muscle mass that accompany it. Stated simply, metabolism is directly linked to muscle mass, so maintaining or even building muscle as we age can help minimize or delay the deleterious effects of the aging process, which for many people is the ultimate goal.