3 Secrets to Burning Fat Effectively

Tips for Getting Your Workout Balance Correct

By Paul Rogers | Reviewed by Richard N. Fogoros, MD Updated December 31, 2017

Burning fat is key to weight loss, body shaping, and improved health or athletic performance. Whether trimming the waistline, smoothing the love handles or losing the cellulite, we all know we should do it but rarely do it right.

The solution lies largely in our understanding of human physiology and what is needed to achieve that “sweet spot” where we burn more fat than we consume.

Why Dieting Doesn’t Work

It is all about energy in and energy out.

The body is a system of which fat is a part. You need to work within that system to understand the role that fat plays and why it can sometimes accumulate excessively.

The body normally burns fat and a mixture of carbohydrates, in the form of glucose, for fuel. The level by which these fuels are consumed is based largely on your physical activity and the number of fats and carbohydrates you consume. When you are at rest, the body will store these fuels for future use. When you are active, the body will turn to these reserves for fuel.

The problem arises when you take in more energy through food than you consume through exercise. Often within a short period of time, the fat and glucose can accumulate to a point where you not only gain weight but begin to develop glucose intolerance.

When this happens, people will often make the mistake of cutting out all carbohydrates and all fats, assuming that the body will burn off the reserves on its own.

Small Steps for Lasting Health

When it comes to new year’s health resolutions, focus on the small things that can be easily maintained year round. Follow this month-long guide for daily tips.

The problem with this is that, by starving yourself, your body will start breaking down its own tissues to keep the system going. This means that whenever the glucose reserves are used up, the body will start breaking down the proteins in muscles to create new glucose molecules to keep itself going.

In essence, the body will be eating itself up. And, while some fat loss will be achieved, it will mostly at the expense of lost lean muscle mass.

It is only by combining a well-balanced diet with exercise that you can burn those fat reserves while providing your muscles the proteins needed to remain strong.

Finding Your Fat Burning Zone

Once you hit upon the correct diet (consisting of quality proteins and a reasonable amount of fat and carbs), you will need to structure an exercise program with right intensity and time to achieve the ideal fat burning zone.

The fat burning zone can differ from person to person. Generally speaking, it implies a slower pace over a longer period of time (90 minutes or more). But this is not always the case.

Even at a faster pace, you will burn some fat, albeit less than you would glucose. This may be appropriate if you are a seasoned athlete who needs to shed a few pounds. If, on the other hand, you are less fit and have considerably more weight to lose, your ideal fat burning zone would involve a slow and steady approach.

To illustrate the difference:

- Walking on a treadmill for 30 minutes burns 180 overall of which 108 constitute fat (40 percent glucose and 60 percent fat).

- Running on a treadmill for 30 minutes burns 400 calories of which 120 constitute fat (60 percent glucose and 40 percent fat).

Why Weight Training Is Needed to Burn Fat

There is another maxim to remember when trying to trim those extra inches: more muscle burns more fat. What this means is that, if you are able to achieve the right intake of protein and exert the right amount of effort to build muscle, all that is really left to burn is glucose and fat.

This would require you to incorporate exercises that build muscle rather than just sweat. While step and spin classes are great ways to burn fat, they cannot do it as effectively on their own, particularly around the waist, trunk, and upper body.

For this, you would need to combine a cardio workout with a structured weight training program.

Why? Because lifting weights moves you quickly into a high-intensity zone, albeit for shorter bursts. While working on a treadmill, cycle, or row machine can burn a lot of calories, if your goal is to burn fat, you need to address your muscle-fat ratio.

What this means is that you need to build more muscle in relation to your body fat. If you don’t, you may lose weight but fail to achieve the tone needed to refine the waist, hips, buttocks, thighs, legs, and upper body.

Summing Up

The practical approach to burning fat (as opposed to shedding a few pounds) relies on three basic tenets, whether you are new to training or an experienced athlete:

- Increase muscle with weight training. Extra muscle burns more energy both during activity (the active metabolic rate) and at rest (the resting metabolic rate). Cardio alone usually can’t accomplish this, and dieting definitely won’t.

- Lift heavier weights. This means finding weights that allow you to complete eight to 12 reps with enough effort to be challenging but not too much as to lose form. If you are able to manage 15 to 20 repetitions, you won’t build muscles and would be better served doing just cardio.

- Incorporate higher intensity cardio. High-intensity exercise, even if only in short bursts, may help rev up the metabolism quickly, particularly at the start of a workout. But don’t overdo it. Keep the intensity within your recommended maximum heart rate, and remember that fat burning requires the right amount of intensity and time.

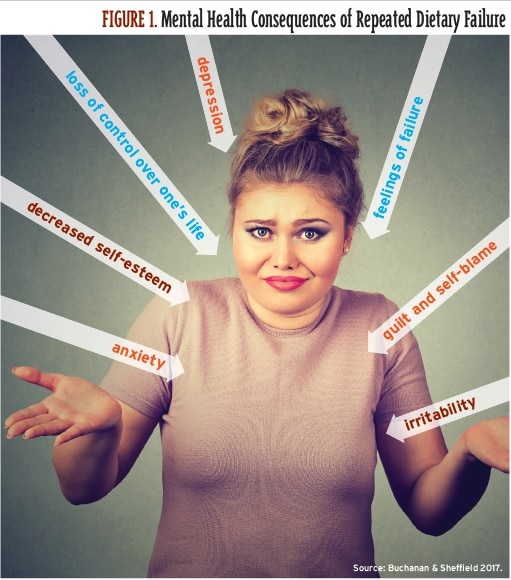

For the first time ever, overeating is a larger problem than starvation among the world’s overall population (Buchanan & Sheffield 2017). Losing weight—and, perhaps more importantly, not regaining it—is a challenge facing millions of people worldwide. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), global obesity rates have nearly tripled since 1975. Further, 1.9 billion adults, 18 years and older, were overweight in 2016. Of these people, more than 650 million were obese (WHO 2017). In 2013, the American Medical Association House of Delegates declared obesity a “disease” requiring treatment because of the multiple medical, functional and psychological complications associated with it.

For the first time ever, overeating is a larger problem than starvation among the world’s overall population (Buchanan & Sheffield 2017). Losing weight—and, perhaps more importantly, not regaining it—is a challenge facing millions of people worldwide. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), global obesity rates have nearly tripled since 1975. Further, 1.9 billion adults, 18 years and older, were overweight in 2016. Of these people, more than 650 million were obese (WHO 2017). In 2013, the American Medical Association House of Delegates declared obesity a “disease” requiring treatment because of the multiple medical, functional and psychological complications associated with it.