Review research about why diets and dieters continue to fail, and learn how small changes can lead to big results.

For the first time ever, overeating is a larger problem than starvation among the world’s overall population (Buchanan & Sheffield 2017). Losing weight—and, perhaps more importantly, not regaining it—is a challenge facing millions of people worldwide. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), global obesity rates have nearly tripled since 1975. Further, 1.9 billion adults, 18 years and older, were overweight in 2016. Of these people, more than 650 million were obese (WHO 2017). In 2013, the American Medical Association House of Delegates declared obesity a “disease” requiring treatment because of the multiple medical, functional and psychological complications associated with it.

For the first time ever, overeating is a larger problem than starvation among the world’s overall population (Buchanan & Sheffield 2017). Losing weight—and, perhaps more importantly, not regaining it—is a challenge facing millions of people worldwide. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), global obesity rates have nearly tripled since 1975. Further, 1.9 billion adults, 18 years and older, were overweight in 2016. Of these people, more than 650 million were obese (WHO 2017). In 2013, the American Medical Association House of Delegates declared obesity a “disease” requiring treatment because of the multiple medical, functional and psychological complications associated with it.

There are numerous “remedies” for being overweight or obese. People buy the newest weight loss books, cut out sugar, eat low-fat and/or low-carb diets, and try the latest quick-fix weight loss products or programs. Yet none of these “solutions” has resolved the obesity epidemic.

This article presents an energy balance update and contemporary understandings of why diets don’t work and why people are missing the mark. Fitness professionals can use the 50 easy-to-implement calorie-cutting ideas presented, along with information about the evidence-based small-steps approach, to help clients start off the New Year with a personalized, realistic and long-lasting healthy eating plan.

Why Do Diets Fail?

Dieting can be defined as a deliberate attempt to restrict food consumption and achieve (or maintain) a desired body weight (Buchanan & Sheffield 2017). The inherent message in many diet plans is that certain foods or food groups are making us fat, and we must largely or completely avoid them. Although numerous plans claim to be medically sound, the associated long-term, health-related benefits are incomplete, and the restrictive nature of these plans makes them difficult to follow and maintain. However, the diet industry continues to be focused on which foods we should eat. While this appears to be a successful sales and marketing approach, it doesn’t educate people about the negative effects of consuming large quantities of food and sugary drinks, a primary factor in ongoing global weight gain. The fact is, “The development of obesity by necessity requires positive energy imbalance over and above that required for normal growth and development” (Hall et al. 2012). There’s no way of getting around it—a person who eats and drinks too much is going to gain weight, and a person who seeks to lose weight must limit calorie intake.

What Do We Know About Dieters?

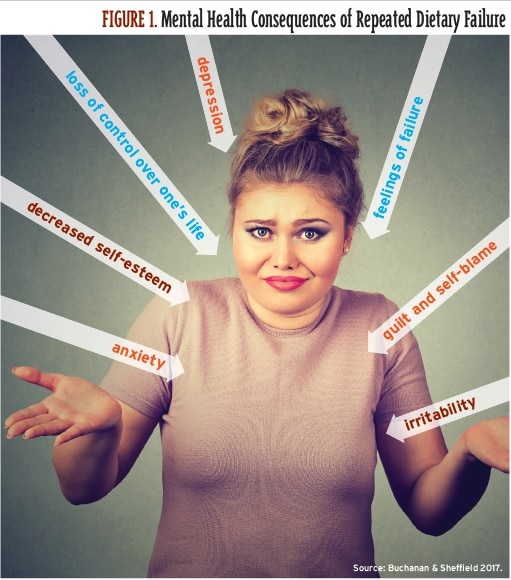

After decades of research investigating “the battle of the diets,” a new line of study is examining the psychosocial factors linked to successful and unsuccessful dieters (Buchanan and Sheffield 2017). Recent findings submit that a key factor in dietary success is adherence to the diet. Successful dieters have resilient adherence; how or why they develop this commanding capacity is yet to be determined.

This pioneering research also indicates that people who fail at dieting often adopt an “all-or-nothing” approach, thinking in a dichotomous way (i.e., their thoughts go in two directions) (Buchanan & Sheffield 2017). By contrast, those who are successful tend to think about dieting as a process in a continuum of changes. Personal trainers who work with dichotomous-thinking clients should acknowledge small weight management victories and openly discuss lapses in an effort to teach clients that successful weight management includes ups and downs. The research by Buchanan and Sheffield offers other insightful findings that can be helpful in client interactions (see the sidebar “Research Findings on Why Dieters Fail”).

Revisiting the Three Components of Energy Balance

Consumption of fat, protein and carbohydrate not only provides energy for daily living but also determines a person’s weight. A lean adult stores about 130,000 kilocalories of fat and may have ~35 billion adipocytes (fat cells), while an extremely obese individual can store ~1 million kcal of fat and may have ~140 billion adipocytes (Hall et al. 2012). Fat is stored primarily in the form of triglycerides.

Carbohydrate is stored as glycogen, which is bound to water, in the liver and muscle. Changes in carbohydrate storage often result in sizable shifts in fluid storage. The more carbohydrates are eaten and stored, the more fluid the body retains. Fat, by contrast, does not need any water to bind with it for storage in the body, and protein needs very little water. Therefore, a person who eats a higher percentage of carbohydrate (not necessarily more calories) will retain more water, thus increasing total body weight.

As little as 2%–10% of total food intake becomes waste and is excreted. The rest is absorbed and oxidized for energy, including growth, physical activity, cell maintenance, pregnancy and lactation, and other biological life processes. These physiological processes are fueled by the energy harnessed from fat (9 kcal/gram), carbohydrate (4 kcal/g) and protein (4 kcal/g). Some foods, depending on the type of fiber content they have, are not digestible and are thus not absorbed and used by the body (Hall et al. 2012).

Hall et al. explain that common energy balance components of interest in weight management include resting energy expenditure (REE), thermic effect of food (TEF) and activity energy expenditure (AEE). REE is the energy needed throughout the day to stay alive and does not include energy used for exercise. It represents two-thirds of the body’s energy needs and can vary widely between people, primarily according to body size (the greater the body mass area, the greater the REE needed to stay alive) and body composition (muscle versus fat). Resistance training, when performed regularly, directly affects muscle mass and may influence (i.e., increase) a person’s REE. The heart, brain, liver and kidney, which weigh relatively minor amounts, demand substantial energy for life and contribute pointedly to the body’s total REE. Interestingly, scientists believe that approximately 250 kcal/day of REE are not fully accounted for by differences or variabilities between people.

TEF is linked to food processing and digestion. Owing to its dietary composition, protein elicits the highest TEF, followed by carbohydrate and then fat. TEF varies between individuals. AEE is the fuel used by the body via structured exercise and nonexercise movement (such as moving, shopping and completing daily chores). This is the factor with the greatest observable range, as many people move a lot during their waking day and exercise regularly, while others don’t move much at all (Hall et al. 2012).

The Small-Changes Approach to Combating Obesity

The small-changes approach was originally designed to support small lifestyle changes and prevent gradual weight gain (Hill 2009). It has evolved to be a wide-ranging strategy that incorporates minor changes in diet and physical activity to combat overweight and obesity. The concept is that small changes, such as cutting calories or making food substitutions, are much easier to implement and maintain than many traditional dietary interventions.

Four Reasons Why the Small-Changes Strategy May Work

A 17-member task force from the American Society for Nutrition, the Institute of Food Technologists and the International Food Information Council evaluated the efficacy of the small changes obesity intervention. According to Hill, there are four major reasons why this approach may succeed:

- Small changes are more realistic to achieve and maintain than large ones. From years of research and observation, the committee concurred that large behavioral and lifestyle changes are the most difficult to sustain. However, small changes—such as simple food substitutions (i.e., replacing a 12-ounce regular soda with a glass of water with lime)—are quite doable and maintainable.

- Even small changes influence body weight regulation. Hill contends that most people in the United States gradually gain weight over time. He explains that a slight increase in energy intake (diet) combined with a slight reduction in energy output (exercise and physical activity) can be enough to create an “energy gap” of 100 kcal/day, with a stored body fat efficiency of about 50 kcal/day. Thus, as a mean average, countless people are gaining about 2 pounds (or more) of fat per year (Hill 2009).

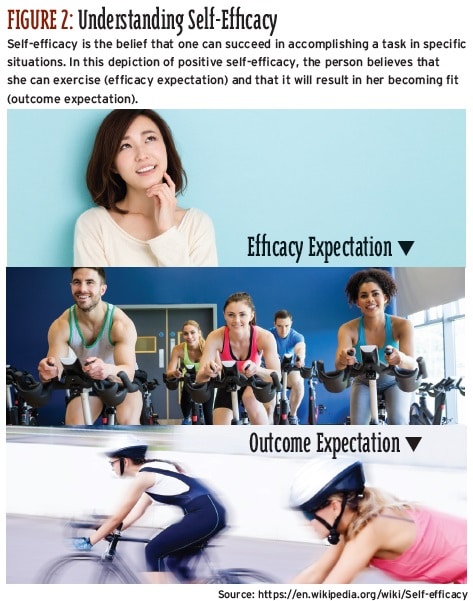

- Small, successful lifestyle changes improve self-efficacy. Self-efficacy is a person’s own sense of being capable of performing in a certain manner (in this case, making small lifestyle changes) to attain certain goals (in this case, losing weight and preventing weight regain) (see Figure 2). The task force suggests that positive changes in self-efficacy may motivate people to greater weight loss progress.

- The small-changes approach may be applied to environmental forces. Through triumphant marketing campaigns, business entities such as restaurants, food industries and fast-food establishments have created environmental cues that encourage excessive food intake. It is hoped that the small-changes approach can successfully restrain these environmental forces (see the sidebar “The Balance Calories Initiative” for one example).

The NEAT Approach: More Moving, Less Dieting

In 2005, James Levine and colleagues introduced the concept of nonexercise activity thermogenesis (NEAT), initiating a new line of research that has investigated the role of daily posture changes—standing, walking and moving—in combating weight gain and obesity. Levine and his team explained that NEAT comprises the energy expenditure of all nonplanned physical activities/exercises. They determined that in men and women who don’t exercise but who actively move during the day, NEAT contributes an additional 350 kcal of energy expenditure per day. Since the introduction of NEAT in 2005, scientists have sought to identify an optimal dose to recommend. (See “A Smart Way to Move” in the September 2017 issue of IDEA Fitness Journal to learn more about NEAT.)

Positive Lifestyle Changes

“Obesity is preventable” (WHO 2017). This is a crucial message for fitness professionals to convey to clients, along with the mindset that healthy eating is a habit, not a diet. With diligence and dedication, fitness professionals are leading the way to creating a healthier society. Encourage small changes to pave the way for big winning moments, one client at a time.

References

Alliance for a Healthier Generation. 2016. Alliance for a healthier generation and American beverage association issue first progress report on reducing beverage calories. Accessed Oct. 2, 2017: healthiergeneration.org/news__events/2016/11/22/1646/alliance_for_a_healthier_generation_and_american_beverage_association_ issue_first_progress_report_on_reducing_beverage_calories.

American Medical Association House of Delegates. 2013. Recognition of obesity as a disease. Resolution 420 (A-13), 2013. Accessed Oct. 24, 2017: npr.org/documents/2013/jun/ama-resolution-obesity.pdf.

Buchanan, K., & Sheffield, J. 2017. Why do diets fail? An exploration of dieters’ experiences using thematic analysis. Journal of Health Psychology, 22 (7), 906–15.

Hall, K.D., et al. 2012. Energy balance and its components: Implications for body weight. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 95, 989–94.

Hill, J.O. 2009. Can a small-changes approach help address the obesity epidemic? A report of the Joint Task Force on the American Society for Nutrition, Institute of Food Technologists, and International Food Information Council. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 89, 477–84.

Levine, J.A., et al. 2005. Interindividual variation in posture allocation: Possible role in human obesity. Science, 307, 584–86.

WHO (World Health Organization). 2017. Obesity and overweight. Accessed Oct. 24, 2017. who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs311/en/.

Young, L R. 2005. The Portion Teller. New York: Morgan Road Books.

IDEA Fitness Journal, Volume 15, Issue 1