Banana-Cocoa Soy Smoothie

With plenty of protein from both tofu and soymilk, this banana-split-inspired breakfast smoothie will keep you satisfied until lunchtime.

Nutirion Profile: Diabetes Appropriate Gluten Free Diet Healthy Weight Heart Healthy High Fiber High Potassium Low Calorie Low Cholesterol Low Sat Fat Low Sodium

Serves Prep Time Total Time

1 5 min 1 hr

Directions

Ingredients

1 banana

1/2 cup silken tofu

1/2 cup soymilk

2 tablespoon unsweetened cocoa powder

1 tablespoon honey

Cooking Instruction

Step 1

Slice banana and freeze until firm. Blend tofu, soymilk, cocoa and honey in a blender until smooth. With the motor running, add the banana slices through the hole in the lid and continue to puree until smooth.

Nutrition

Serving: Per serving

Calories: 340

Carbohydrates: 60g

Fat: 8g

Protein: 17g

Dietary Fiber: 10g

Saturated Fat: 1g

Monounsaturated Fat: 1g

Cholesterol: 0mg

Potassium: 749mg

Sodium: 121mg

Exchanges: 1 1/2 fruit, 1/2 reduced-fat milk, 1 1/2 other carbohydrate, 1 medium-fat meat

Carbohydrate Servings: 3

By Matthew Kadey, MS, RD | March 21, 2019 | 1

There’s another reason to make sure you’re getting enough of the sunshine vitamin: High levels of vitamin D in the blood are now linked with better fitness, according to research from the Virginia Commonwealth University School of Medicine. In the study, published in the European Journal of Preventive Cardiology, 20- to 49-year-olds with better vitamin D status also tended to have greater cardiorespiratory fitness, a measure of aerobic fitness often determined by measuring maximal oxygen consumption (VO2max) during exertion.

Muscle cells have receptors for vitamin D; that might explain why this nutrient can influence athletic performance. Admittedly, the study showed only an association between vitamin D and cardiorespiratory fitness and did not prove that high vitamin D levels increase people’s ability to run harder for longer. Even so, it seems like a good idea for fitness-minded folks to make sure they get enough vitamin D via safe amounts of sun exposure, dietary sources like fatty fish and fortified dairy, and supplementation if a physician or dietitian deems it necessary.

by American Council on Exercise

on February 22, 2021

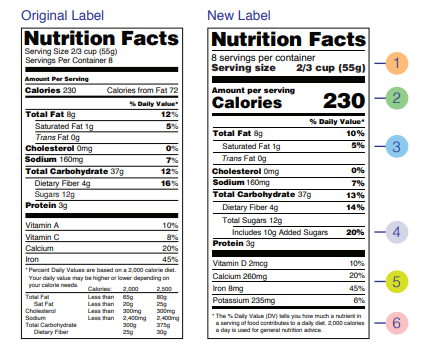

Imagine a world where packaged foods and drinks do not contain consistent and uniform nutrition facts labels. Consider how challenging it would be to make healthy food choices regarding the quality and quantity of the foods you consume. This was the case before 1990, when the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) passed the Nutrition Labeling and Education Act (NLEA). Since then, several iterations of nutrition facts labels have taken form, and, by the mid-1990s, most food packaging contained the iconic black and white label that most people recognize.

However, if you are a keen observer, you may have recently noticed changes to the nutrition facts label on some of the foods you purchase. In 2016, significant updates to the label were initiated for the first time in more than 20 years and food manufacturers are working together with the FDA to ensure a complete update by July 1, 2021. The nutrition facts label is being updated based on new nutrition research, updated scientific information, and input from the public, all to make it easier for consumers to make informed food choices to better support a healthy diet. This is all part of the FDA’s ongoing public health efforts to reduce nutrition-related preventable death and disease and to help individuals maintain healthy dietary practices.

They are not a recommendation for how much a person should consume. For example, the serving size for soda has changed from 8 ounces to 12 ounces not to encourage the consumption of more soda, but instead to better represent how much soda is typically consumed as a single serving. In addition, the declared serving size now appears in a larger and bolder font. If a food package contains an amount that is between one and two servings, such as a 15 ounce can of soup, it is required to be labeled as one serving because people typically consume the whole can.

This change makes this information easy to find, which can be very helpful when comparing foods in the store or when keeping track of calories consumed.

This addition to the label aligns with a key focus from the 2020-2025 Dietary Guidelines for Americans for limiting foods and beverages higher in added sugars, with a recommendation to consume less than 10% of calories per day from added sugars. If you consume more than 10% of calories from added sugars, it is hard to meet nutrient needs while staying within calorie limits.

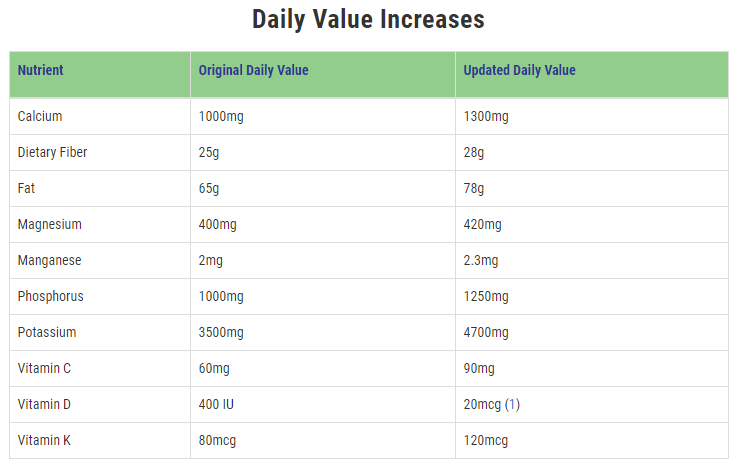

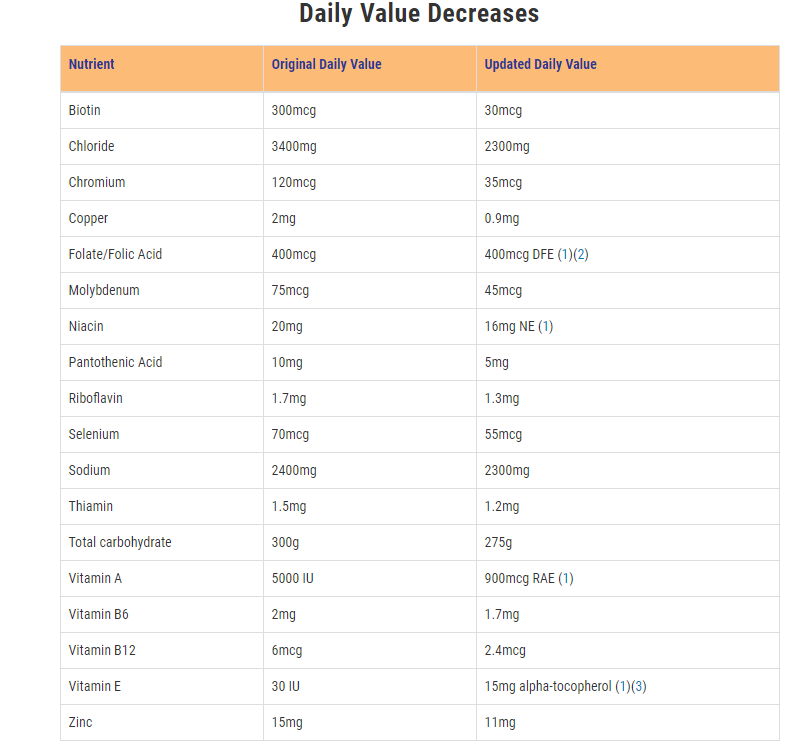

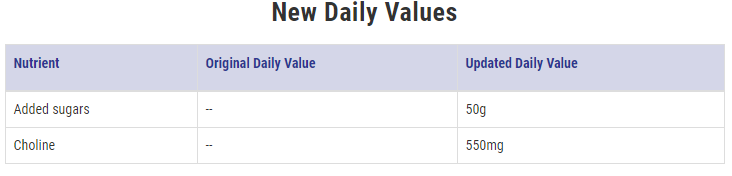

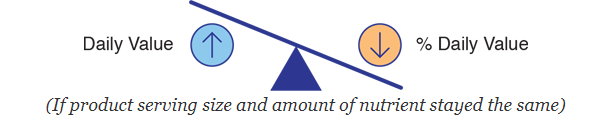

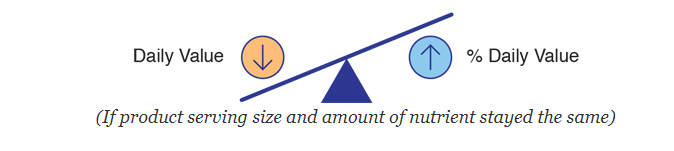

Luckily, ensuring an adequate amount will now be easier with the requirement that potassium and vitamin D appear on the label. Additionally, not only must a percent daily value be provided for vitamin D, potassium, calcium, and iron, but the actual amount must also be provided. Vitamins A and C are no longer required to appear on the label because deficiencies of these nutrients are rare. Also, it is important to note that new scientific evidence has led to higher and lower percent daily values for certain nutrients (Tables 1 and 2). For example, the percent daily value for total fat has increased from 65 grams to 78 grams, meaning that if a packaged food contains 40 grams of fat in one serving it would have previously been labeled as 62% of the daily value and now it would be labeled as 51% of the daily value. In addition, added sugars and choline now have percent daily values (Table 3). Figures 1 and 2 depict the relationship between daily value and percent daily value—as one increases, the other increases.

This helps individuals more clearly understand nutrition information in the context of total daily calories consumed.

Reading the nutrition facts label may seem like a daunting task, but it can help you make informed dietary decisions as part of a healthy eating pattern and avoid nutrition-related health concerns. To practically apply this information and better understand how the label relates to your daily food intake, please visit MyPlate.

by Justin Robinson

on October 06, 2020

Vegetarian, vegan, plant-based, all similar terms with some distinct differences. It can be confusing to know which approach is the best for you, especially if you’re trying to make some healthy changes. This article examines the differences between these diets and looks at the available research on the benefits of making the switch to a diet that is focused primarily on plants (and may or may not eschew meat altogether).

Vegetarian diets usually include all fruits, vegetables, grains, legumes, nuts and seeds, and may include eggs and dairy products. All of these diets typically exclude all meats (flesh). Plant-based is an encompassing term for vegan and vegetarian diets that are defined by the type or frequency of animal product(s) consumed. There also are subsets within these diets, which are defined by the types of animal-based products that are consumed or avoided:

Given this range of plant-based classifications, it can be difficult to determine from the available research exactly which types provide the most health benefits. Cardiovascular disease (CVD), for example, takes years to develop, so a well-controlled, short-term study cannot adequately assess CVD risk. Therefore, we must rely on examining the correlations between dietary habits and health factors. Overall, a well-planned and executed vegetarian diet can provide adequate nutrition, promote overall health and lower the risk of major chronic diseases.

Let’s take a look at some of the specific health benefits of following a plant-based diet.

Eating a variety of vegetables and whole fruits is a key recommendation of healthy eating patterns. A varied consumption of fruits, vegetables, whole-grains, legumes and nuts at an appropriate calorie level usually leads to an adequate intake of dietary fiber and a low intake of saturated fat and hydrogenated vegetable oils. As a result, vegetarians commonly have lower body mass indexes (BMI), LDL-cholesterol, blood pressure and reduced rates of stroke, type 2 diabetes, certain cancers, and death from heart diseasethan do non-vegetarians.

Further, vegetarian eating patterns are rich in health-promoting phytochemicals and vitamins C and E, which function as antioxidants to protect against oxidative stress. Additionally, these eating patterns provide magnesium and potassium rich foods which can improve insulin sensitivity and vascular function, respectively The dietary fiber along with phytochemicals can help improve and maintain gut the microbiome.

To summarize, potential mechanisms for improved health from vegetarian eating plans include weight loss/maintenance, blood sugar control, improved lipid profile, reduced blood pressure, decreased inflammation and improved gut health.

Several dietary factors in animal foods have been associated with increased risk of CVD. Historically, saturated fats, prevalent in meats, have been linked to elevated cholesterol and other unfavorable disease risk profiles. Interestingly, saturated fats themselves may not be responsible for many of the adverse health effects that they have been associated with, but rather the processing of meats may be at fault. Consuming preservatives in processed meats, such as sodium, nitrates and nitrites, may raise blood pressure and impair insulin response.

Most research shows a sliding scale of improved health outcomes from increased plant intake with decreased meat intake. Completely eliminating meat and dairy products may not be necessary for good health, however, as they can be part of a healthy eating pattern. Choosing whole foods over processed foods also is an important strategy for maximizing the health benefits from any diet plan.

As mentioned, the term “vegetarian” can mean a lot of things to a lot of people, as vegetarians exhibit diverse dietary practices. Here are some suggestions for making the shift toward a plant-based diet:

As with any diet plan, there are healthy and less-healthy versions of vegetarianism, and being any type of vegetarian by name does not guarantee the health benefits discussed earlier. Soda, cookies, French fries, macaroni and cheese, and sugary cereals are all vegetarian foods. Certainly, a vegetarian diet can be high in calories, sugar, preservatives and unhealthy fats. Also, strict vegetarian diets can omit certain nutrients, primarily omega-3 fatty acids, calcium, vitamin D, iron, zinc and vitamin B12. Constructing a healthy vegetarian diet includes meal planning and preparation to avoid missing out on important nutrients.

A plant-based diet may also need to include fortified foods (i.e., vitamins and minerals added to the product) and potentially supplementation. Vitamin B12, specifically, is only obtainable through animal foods or dietary supplements. Eggs and milk, however, contain B12; thus, a lacto-ovo-vegetarian will have fewer nutrient gaps to fill than a vegan.

Consuming adequate amounts of vegetables and fruits is, in fact, the strongest correlate with reduced disease risks, particularly CVD (USDA, 2015). A healthy diet (including or excluding meat products) should include more vegetables and fewer processed foods. Regardless of which dietary approach you follow, make healthy eating a lifestyle that you can follow for years to come.

By Matthew Kadey, MS, RD

Jul 6, 2021

Going from meat to vegetarian or vegan diets may result in a surprising and troubling change in the types of foods people choose to add to their diets. In a study published in The Journal of Nutrition, researchers divided more than 21,000 adults into four groups—meat eaters, pesco-vegetarians (whose diet includes fish), vegetarians and vegans—and analyzed daily food intake.

The study found that those who followed vegetarian and vegan diets appeared to consume more ultraprocessed foods (UPFs). These are packaged foods like potato chips, ice cream, and the new wave of engineered meat and dairy substitutes, like foods made from textured soy protein and plant-based drinks made from soy, almond or rice. Those who initiated a meat-free diet at a younger age were more likely to include more UPFs in their diet.

Those who believe that steering clear of meat and dairy is enough to improve health should also check out a separate investigation, published in the International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. Using 13 years of data from nearly 92,000 people, this study found that those with the highest likelihood of cardiovascular-related death in that time frame were more likely to eat the most UPFs.

The takeaway here is that people pondering a plant-based lifestyle need to be educated on how to meet their nutrition needs using predominantly whole-food options.

By Catherine Reade, MS, RD

Sep 7, 2021

Armed with a little bit of knowledge, home cooks can use simple cooking techniques and tips to boost the nutritive aspects of the food they prepare. However, this also works in reverse. Without knowledge, certain cooking techniques, pots, pans and utensils can actually diminish the nutrients you get from the meals you so painstakingly prepare.

In today’s busy world, those of us who take the time to shop for fresh ingredients and then cook well-balanced, healthy meals want to ensure we’re getting the biggest nutrient bang for our efforts. Learn these few tricks of the trade, share them with clients and bring them to your home kitchen.

“Preparing food at home provides control over what we—and our family—are eating,” says Pat Baird, MA, RD, a nutrition consultant and author in Greenwich, Connecticut. Experienced cooks use certain techniques to greatly influence the taste, texture, aroma, color, safety and nutrient value of food. This process starts with knowing the best cooking techniques and tips food preparation and storage methods.

When foods are cut, the area scored is similar to a wound: This is where the most nutrients leach out or “bleed” from! That’s why it is advisable to leave foods whole or in the largest pieces possible. It is also why you should always turn food—especially meats and poultry—with tongs or a spatula rather than a fork during cooking. This way you avoid piercing the food and releasing its nutritious juices. Whenever possible, cook fruits and vegetables with their skins intact; these skins act as a protective coating, which helps retain nutrients.

Time is also a nutrient killer. The longer foods are stored, the more the nutrients break down. Cook foods as soon after purchase as possible and eat any leftovers within a few days. Safety is also an issue here; to prevent bacterial growth, food should always be kept at below 40 degrees Fahrenheit (˚F) and cooked at above 140˚F.

As a rule, rapid cooking techniques are better for retaining nutrients than slower methods. In fact, spending the least amount of time cooking is the way to go. Any type of cooking changes food in some ways. In general, nutrients are lost when food is exposed to heat, light, moisture and air (Robertson 1986). The longer food is exposed to these factors, the greater the nutrient loss. To retain the most nutrients possible, most experts recommend that you cook food thoroughly but rapidly.

The cooking techniques that typically preserve nutrients best can be ordered from quickest to slowest, as follows:

The nutrient retention achieved through these cooking techniques may vary according to the food type, size and shape and your own cooking technique. Note that boiling is not a preferred cooking technique because it does the most nutrient damage (Robertson 1986). This is especially true when foods are boiled in too much water, which is then poured down the drain (along with the nutrients themselves!). A practical way to recoup the nutrients that are released into boiling water is to retain the liquid after cooking and use it as stock for soups.

A pressure cooker (Instant Pot) is a pot outfitted with a locking lid. This device cooks food quickly and healthfully by creating steam under pressure, thereby increasing the cooking temperature. Foods that are the best candidates for this cooking technique are dried beans, grains and vegetables.

When using a pressure cooker, timing is essential since vegetables can become overcooked in seconds! It is also important to use precisely the amount of liquid called for in the recipe. When you are cooking grains or beans, allow enough room for them to expand; do not fill the cooker more than half full. To prevent beans and grains from foaming over, add a few teaspoons of oil (Margen et al. 1992). (Cooking in high altitudes will require more liquid and a longer cooking time.) For best results, be sure to follow the instructions that come with the pressure cooker.

Can anyone imagine life without the microwave now that we have become accustomed to its speed and convenience? Microwaving uses electromagnetic radiation to heat foods (McGee 1984). Water in the food is the predominant molecule affected in this process; the water moves back and forth rapidly, creating energy that causes the temperature of the food to rise quickly.

Microwaving is an undeniably fast cooking technique that uses a minimum amount of liquid, producing great-tasting vegetables and fish. However, this method is less successful for cooking meat and poultry. Quick heating can cause greater fluid loss and result in a drier texture. Also, meats and poultry can’t be browned as they can with other cooking techniques, since the food’s surface never gets any warmer than the interior; this affects both the flavor and the appearance of foods (McGee 1984).

Little is known about the long-term safety of microwaving food. Concerns have been expressed about microwaves altering the protein chemistry of foods in ways that may be harmful (Weil 1997). For this reason, some health experts recommend using the microwave only for rapid heating and defrosting, not for longer cooking.

One major health concern tied to microwaving involves the use of plastic containers or plastic wrap—even those types labeled “microwave safe.” It appears that chemicals from the plastics (known as “plasticizers”) can migrate into food and may eventually interfere with the body’s hormonal balance, contributing to birth defects, reproductive abnormalities, early puberty in girls and some hormone-dependent cancers (Walsh 1998; Welland 2000). Heat and light accelerate this potentially detrimental process (Welland 2000). The hotter the food is, the greater the risk of these plastic particles melting into the food. To avoid this danger, use glass or ceramic containers like Pyrex™ or Corningware™, which do not react with food. To keep food moist, cover it with a glass or ceramic lid, paper towel or wax paper.

This healthful cooking technique retains most nutrients, since the food is not immersed in water. Almost any food that can be boiled can be steamed, especially any type of vegetable. Invest in a metal steaming basket or bamboo steamer or improvise using a metal colander in a pot topped with a tight-fitting lid. A large steamer pot is ideal since it provides ample space for the steam to circulate, cooking the food most efficiently. Water will boil away as the food is cooking, so be sure to start off with enough liquid in the pot.

See also: Steamed Lemony Tilapia Recipe

Traditionally an Asian cooking technique, stir-frying rapidly cooks small, uniform-sized pieces of foods, most commonly mixed vegetables. Thinly sliced pieces of beef, chicken or shrimp can also be stir-fried in a wok or large, nonstick frying pan. Stir-fried meals are healthful because foods cook rapidly at relatively high temperatures. Very little oil is needed with this cooking technique, just enough to form a thin film on the pan (Hensrud et al. 1998). If desired, broth, wine or nonstick cooking spray can be used instead of oil. (Just be sure to add more liquid to the pan as it evaporates.) Gradually add the oil or broth to the pan, heating until hot but not smoking. Then toss in the food and stir constantly until meats are thoroughly cooked and vegetables are just tender and crisp (Margen et al. 1992).

Both of these cooking techniques expose food to direct heat, leaving food crispy on the outside and juicy on the inside with a characteristically intense flavor. These methods work well with meat, seafood, poultry, vegetables and even fruit! For best results, meat should be cut in chunks 1 to 2 inches thick; however, leaner meats, such as chicken or fish fillets, can toughen and overcook under such high heat. Depending on the food’s thickness and the heat intensity radiated by the broiler or grill, position meat about 4 inches from the heat source; place chicken and fish about 6 to 8 inches away (McGee 1984; Margen et al. 1992). For a great marinade recipe that can be used on most grilled or broiled foods, see the “Marvelous Marinade” sidebar.

Sturdy vegetables can also be broiled or grilled. However, this works best if the veggies are in fairly large pieces (like whole baby carrots or mushrooms), thickly sliced (like red potato wedges) or cut in half (like eggplant). You can either marinate the veggies and cover them with aluminum foil or brush them lightly with oil and put them in a wire basket, which can be easily turned during cooking. Place the vegetables about 4 inches from the heat source and, as the veggies cook, baste them once or twice with broth, marinade or juice. When they begin to brown, turn them over to lightly brown the other side (Margen et al. 1992).

When broiling, use a pan with a rack to allow the fat drippings to slip through; this will lower the fat content of meat and prevent flare-ups caused by dripping fat. Although grilling causes fat to drip away, flare-ups when barbequing can result in harmful substances forming on meat. The smoke coats the barbequed food with polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), which may promote cancer (Golub 2001). The high temperatures of grilling (and broiling) can also cause carcinogenic substances called heterocyclic amines (HCAs) to form on the surface of well-done and charred meat (Golub 2001). For tips on how to grill more safely, see “Healthy Barbequing Tips.”

Sometimes called pan-frying, sautéing rapidly cooks small, uniform-sized pieces of food in little or no oil. The best candidates for this cooking technique are vegetables and thin cuts of meats or seafood, such as pork medallions, boneless chicken breasts and scallops. Traditionally, most cooks have used butter or oil to sauté, but very little fat is needed if a nonstick pan is used (Margen et al. 1992). Depending on the recipe, broth, wine or water can replace all or some of the oil. (Keep in mind, however, that these liquids do not heat as quickly as oil and may slightly alter the cooking process and flavor.) I personally prefer to sauté garlic lightly in olive oil, then add a cut-up vegetable like broccoli (either raw or blanched) for a quick side dish; for an entrée, I add some broth and pasta.

The key to this cooking technique is to use a hot skillet, heating the liquid until hot—but not smoking—so that the food cooks quickly. Once the liquid is hot enough, add the food immediately and stir. To avoid releasing juices (and nutrients), turn meats with tongs or a spatula instead of a fork. If using broth or water in place of oil, replenish the liquid as it evaporates. The pan should be large enough to avoid crowding, or the food will actually steam rather than sauté!

This stove-top cooking technique gently simmers foods in water (or other liquids, such as broth, vinegar, wine, fruit juice or vegetable juice, to add more flavor). Meats, poultry, fish, seafood, vegetables and fruit can be poached. The nutritional advantage to poaching is that the liquid becomes part of the dish itself but contains little or no added fat. The liquid can be thickened by adding flour or cornstarch. To use this cooking technique most efficiently, choose a pan that best suits the size and shape of the food, so a minimum amount of liquid is used; this also minimizes cooking time (Hensrud et al. 1998).

Braising involves slow cooking in a small amount of liquid inside an open or covered pan. Suitable for meat, poultry or vegetables, braising can be done either on the stove top or in the oven (Hensrud et al. 1998). The braising liquid can be water, broth, juice or wine. This is one of the best cooking techniques to tenderize a tough piece of meat, since slow cooking in liquid softens the connective tissue. (Pot roast is a familiar example of a braised meat.) Be aware that fatty, tender cuts of meat will become tough with this cooking method (Margen et al. 1992).

Like baking, roasting uses the dry heat of an oven to slowly cook food such as meat roasts, whole chicken or turkey. However, roasting is typically done at higher temperatures than baking. Almost any kind of fatty or lean meat can be roasted, although this cooking technique works best for larger cuts. Sturdy vegetables can also be roasted to intensify their flavors.

While vegetables can be roasted on a baking sheet, it is best to roast meats in a broiler or in a roasting pan with a rack so that fat can drip away from the meat during the cooking process. For easy cleaning, coat the rack with cooking spray and line the pan bottom with foil. Cooking time will vary with this method, depending on the size, shape and cut of meat. A good meat thermometer inserted into the thickest portion is essential to judge when the meat is cooked thoroughly (Margen et al. 1992).

When we think about this cooking technique, the first foods that usually come to mind are baked goods, such as breads, cookies and cakes. But this dry-heat cooking technique, which cooks food by surrounding it with heated air in an oven, can be used to cook uniform-sized pieces of veggies, fruit, seafood, poultry or lean meat. Baking works well when little or no fat is added to a dish (Margen et al. 1992). Use a shallow baking dish, and cover it with foil or a lid to keep foods moist.

See also: Eating With the Seasons

Like the food you prepare, a quality set of pots and pans is an essential ingredient in any successful recipe. There are two basic qualities to look for in cookware. First, it should be made from a material that conducts heat evenly and efficiently to prevent “hot spots” from developing and food from burning. Second, the pot’s surface should not be chemically reactive, which would allow atoms from the metal to leach into the food, potentially affecting the food’s flavor or color; examples of cookware with this drawback include cast-iron and aluminum pans (Garrison & Somer 1995).

The advantages of aluminum are that it is inexpensive, a very good heat conductor (second only to copper) and lightweight, making it easy to handle (McGee 1984). Unfortunately, food molecules can easily penetrate its surface, particularly acidic ones like tomatoes, alkaline ones like milk and sulfur-rich foods like eggs. These molecules can cause light-colored foods to become noticeably discolored. The sulfur odor that is emitted when cooking foods such as cruciferous vegetables (e.g., cauliflower and broccoli) is also intensified in aluminum pots and pans.

In the 1970s, aluminum cookware was linked to an increased risk for Alzheimer’s disease when Canadian scientists observed a higher than normal level of aluminum in the brain of patients with this disease (Schepers 2000). However, other researchers have been unable to duplicate these results (Schepers 2000). Aluminum cookware and utensils contribute about 2.5 milligrams (mg) of aluminum to the average American’s daily diet. This is small in comparison to food additives and leavening agents, which add 25 to 50 mg of aluminum daily; buffered aspirin, which adds 125 to 725 mg; or common antacids, which add 850 to 5,000 mg. If concerned, avoid aluminum cookware, but be aware that far greater sources of aluminum are regularly consumed without much fanfare (Schepers 2000).

Considered the best heat conductor, copper cooks food quickly and evenly. Unfortunately, it is highly reactive with anything it encounters, including food. To prevent copper from leaching into food, the copper must be coated with stainless steel (Schepers 2000). (Older cookware was often lined with tin, which wore off easily, revealing the copper below.) While copper is an essential mineral, too high an intake can be toxic. Never serve or cook food in unlined copper pots or pans or in utensils whose lining is worn even minimally. Pure copper pots and pans are truly for decorative use only!

Don’t tell Grandma that her old cast-iron skillet is a relatively poor conductor of heat. Chances are, her prized pan is so thick and heavy it will absorb and hold heat well, regardless of its poor conductivity! This makes cast-iron a prize of many cooking techniques. Iron cookware needs to be regularly oiled and gently cleaned to avoid corrosion. This cookware can also leach iron into food, which can be a good or bad thing. Increased iron intake can benefit children, adolescents and menstruating women, who typically need to boost their levels of this nutrient. But older people and those at risk for hemochromatosis (iron overload disorder) should avoid additional dietary iron intake (Schepers 2000).

See also: One Cast-Iron Pan, 5 Recipes from Clean Eating

This cookware is created by placing a nonstick coating (like Teflon®) over metal. The obvious advantage is that this minimizes the amount of fat needed to prevent food from sticking to the pan. However, the coating itself can chip. Although the material is nontoxic and will pass through the body without being absorbed (Schepers 2000), chipping is obviously undesirable and can cause food to be unevenly cooked. To protect the coating, avoid using metal utensils with nonstick cookware. If you have a pot or pan with a significant amount of chipping or peeling, throw the piece away since the damage affects cooking performance.

Although stainless steel is a poor conductor of heat, it is chemically the least reactive of the metals. Stainless steel cookware tends to be expensive, so some manufacturers skimp on the thickness of the metal. A pan that is too thin will create hot spots, causing uneven cooking. The transfer of heat is vastly improved if the pan has a copper or aluminum inner core or if the bottom of the pan is coated with copper (McGee 1984). Despite their inferior heat conduction, stainless steel pots and pans—particularly the hybrids that are “clad” or combined with other metals—are probably the best forms of cookware available today.

Ceramic pots and pans are poor conductors of heat, especially when used on a stove top, so they don’t distribute heat evenly over a surface. Ceramic material is a better choice when used as an oven casserole dish or a Crockpot™, because the heating process is slower and more diffuse. Ceramic pots and pans do retain heat well, making them good candidates for keeping food hot at your next dinner party! However, a word of caution is in order: Do not cook or store food in that beautiful ceramic pottery you purchased on your last trip to Mexico, South America or the Mediterranean! Many of the ceramic items produced in other countries are not fired at high enough temperatures and, as a result, can leach lead from the ceramic glaze into food. Even in small amounts, lead is extremely toxic and can cause brain or nerve damage and impair the immune system (Schepers 2000).

Updated September 8, 2021

Marinades can not only add great flavor to food but also tenderize tougher cuts of meat. From a safety perspective, marinades may help reduce some of the carcinogens that can form on food when it is grilled or broiled (American Institute for Cancer Research 2001).

The following marinade works well when grilling or broiling vegetables, tofu or meats. Slice veggies—such as eggplant, zucchini, summer squash, bell peppers, mushrooms, cherry tomatoes and/or red onion—into thick rounds or, if small, leave whole. Cut lean meat, skinless chicken, seafood or firm tofu into 2-inch cubes.

1/2 cup rice or white-wine vinegar

1 tablespoon canola oil

1/4 cup finely chopped onion

1 small bay leaf

2 sprigs fresh (or 1/2 teaspoon [tsp] dried) rosemary, thyme or oregano

2 cloves garlic, finely minced

1/2 tsp freshly ground pepper

In bowl, combine marinade ingredients until well blended. (Use a nonmetal container to prevent off flavors from forming.) You’ll need about a 1/2 cup of marinade for each pound of food. Add the food and turn several times until all sides are coated. Cover and refrigerate for at least 30 minutes, occasionally turning food so that marinade is distributed evenly. Drain and discard marinade. Thread skewers for meat and vegetables separately or place in aluminum foil or wire baskets (cooking times will vary, depending on the food). Place on grill and turn often with tongs or spatula to prevent charring. If you want marinade for basting, make a second bowl, to prevent spreading bacteria.

Source: American Institute for Cancer Research 2001.

The American Institute of Cancer Research offers these tips for healthier grilling:

American Institute for Cancer Research. 2001. The Facts About Grilling (brochure). Washington, DC: www.aicr.org.

Garrison, R., & Somer, E. 1995. The Nutrition Desk Reference. New Canaan, CT: Keats Publishing.

Golub, C. 2001. Sizzle safely this summer: Tips for great grilling. Environmental Nutrition (June).

Hensrud, D., et al. 1998. The Mayo Clinic Williams-Sonoma Cookbook. San Francisco: Time-Life Books.

Margen, S., et al. 1992. The Wellness Encyclopedia of Food and Nutrition. New York: Random House.

McGee, H. 1984. On Food and Cooking. The Science and Lore of the Kitchen. New York: Collier Books.

Robertson, L. 1986. The New Laurel’s Kitchen. Berkeley, CA: Ten Speed Press.

Schepers, A. 2000. Concerned about your cookware? Environmental Nutrition (May).

Walsh, J. 1998. How your hormones are affected by what you eat.—The debate rages. Environmental Nutrition (February).

Weil, A. 1997. Dangers of microwaves? www.drweil

.com; published April 18, 1997; retrieved December 8, 2001.

Weil, A. 1998. 3 tips for a healthier summer. Self Healing (June).

Welland, D. 2000. Should you ban plastic products from your kitchen? Environmental Nutrition (June).

Catherine Reader, MS, RD, created and runs HealthFull Living™, a nutrition consulting company in Littleton, Colorado, that specializes in nutrition for sports performance, weight management and wellness. She is also an ACE-certified group fitness instructor who has been designing and teaching personalized nutrition and fitness programs for more than 10 years. She can be reached at creade@dimensional.com.

By Matthew Kadey, MS, RD

Aug 9, 2021

Graphic of woman reading a best if used by label

That label you’re looking at: Does it mean “spoiled—toss it out” or “not optimal, but still safe to eat”? Food date labels can play an important role in helping consumers make informed decisions about food and can ultimately prevent unnecessary waste and protect against unsafe consumption. But the streamlined “Use By” and “Best If Used By” label system is still confusing people, signaling a need for better consumer educational communication, according to a study in the Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior.

Less than half (46%) of the 2,607 study respondents knew what the “Best If Used By” label specifically indicated, and fewer than one-quarter (24%) of participants understood the “Use By” label.

Here’s what the labels mean: “Best If Used By” dates are on products with longer shelf lives and refer to the amount of time that the food will be in optimal condition. A product that has passed this date may still be safe to eat, but the quality might not be as good. “Use By” dates are on perishable products with shorter shelf lives, and the date refers to when a product is expected to spoil and be unsafe to eat.

Giving consumers a brief explainer of what each label meant increased the level of understanding. Post-explanation, 82% could correctly articulate what a “Best If Used By” label meant, and 82.4% properly explained what “Use By” signified.

By Matthew Kadey, MS, RD

Jun 4, 2021

Hummus chicken wrap

Here is some sobering news: Nearly half of adults in the United States have hypertension, and nearly half a million deaths yearly have included hypertension as a primary or contributing cause. Perhaps if more people ate foods rich in niacin—including chicken, tuna, salmon, avocado and peanut butter—it would take a bite out of the soaring blood pressure numbers.

According to a study in JAMA Network Open, adults who had an ideal level of dietary niacin intake (between 14.3 and 16.7 milligrams a day) had a lower risk of new-onset hypertension, defined as systolic blood pressure of 140 mm Hg or greater and/or diastolic blood pressure of 90 mm Hg or greater. While this link was discovered among people living in China, it may also apply to Americans at risk of hypertension. That makes these hummus chicken wraps a low-pressure lunch option.

1 bunch asparagus, woody ends trimmed and halved

1 C prepared hummus

4 large whole-grain sandwich wraps

2 C arugula

1 lb cooked and sliced chicken breast

1 C sliced roasted red pepper

2 T fresh lemon juice

Place asparagus in a steamer tray set over 1 inch of water. Bring water to a boil and steam asparagus covered until bright green and tender, about 3 minutes. Spread an equal amount of hummus over the surface of each wrap. Place equal amounts of arugula, chicken, asparagus and roasted red pepper on the bottom third of the wraps. Squeeze on lemon juice. Roll tightly, folding the edges in as you roll, and then slice in half on a diagonal. Makes four servings.

See also: Recipe for Health: Edamame Chicken Wraps

IDEA Fitness Journal SPRINT – June 2021

Matthew Kadey, MS, RD

Matthew Kadey, MS, RD, is a James Beard Award–winning food journalist, dietitian and author of the cookbook Rocket Fuel: Power-Packed Food for Sport + Adventure (VeloPress 2016). He has written for dozens of magazines, including Runner’s World, Men’s Health, Shape, Men’s Fitness and Muscle and Fitness.

The old adage “Breakfast is the most important meal of the day” seems to have some merit. Adults who skip breakfast are 22% more likely to develop cardiovascular disease and 25% more likely to suffer premature mortality than those who typically eat a morning meal. That’s according to a meta-analysis, published in Clinical Nutrition, that examined seven studies (conducted through June 2019) involving a total of 221,732 participants.

Going hungry in the morning may make it harder for people to meet all their nutrient needs for good health or may set them up for less-healthy eating habits later in the day. A growling stomach can be a recipe for making poor food choices.

Of note, this study did not address the types of breakfast foods that provide the biggest longevity benefits. Certainly, rolling out of bed and spooning up a bowl of sugary cereal with a side of bacon would not bring about the same heart-health perks as more wholesome options like oatmeal, fruit and yogurt.

By Sarah Kolvas

Aug 3, 2021

If you want to stay on top of your daily nutrition, consider making your morning meal a priority. Skipping breakfast could mean missing out on key nutrients, creating a nutrition gap for the remainder of the day, according to a study published in Proceedings of the Nutrition Society.

The study was completed with Ohio State College of Medicine graduate students and supported by a regional dairy association. The research team used data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), which collects health information every year on nationally representative samples of 5,000 people through interviews, laboratory tests and physical exams.

This study’s sample included 30,889 adults age 19 and older who participated in the survey from 2005 to 2016. Participants identified their foods as a meal or a snack, and reported the times they ate, which researchers used to determine whether a participant ate breakfast or skipped it. In all, 15.2% of participants—4,924 adults—reported skipping breakfast.

Researchers translated this data into nutrient estimates using the federal Food and Nutrient Database for Dietary Studies and daily dietary guidelines. They then compared those estimates with recommended nutrient intakes from the Food and Nutrition Board of the National Academies.

According to the key recommendations they measured, people who skipped breakfast consumed fewer vitamins and minerals than those who had eaten breakfast, with the most differences found for folate, calcium, iron, and vitamins A, B1, B2, B3, C and D.

Further, participants who skipped breakfast had a poorer nutrient profile for the rest of the day, with higher intakes of added sugars, carbohydrates and total fat due to increased snacking.

“People who ate breakfast ate more total calories than people who didn’t eat breakfast,” noted the study’s senior author, Christopher Taylor. “But the lunch, dinner and snacks were much larger for people who skipped breakfast, and tended to be of a lower diet quality.”

While the study only reviewed a single day in each participant’s life, the analysis still showed that missing nutrients in breakfast foods—like calcium in milk, vitamin C in fruit, and fiber, vitamins and minerals in cereals—reduced nutrient intake for the rest of the day.

“What we’re seeing is that if you don’t eat the foods that are commonly consumed at breakfast, you have a tendency not to eat them the rest of the day,” explained Christopher. “So those common breakfast nutrients become a nutritional gap.”

The data suggests a morning meal may be helpful in avoiding excessive snacking, and improving overall nutrition.